Coronavirus

Since the start of 2020 coronavirus has hit the world and caused unprecedented levels of concern among public and health professionals alike.

This is an evolving field. Until identification in China in December this was an unknown pathogen. What we discuss here today may be out of date in a week or even a day. With this in mind, at the end of this chapter we include a range of resources that frequently update as our understanding of the disease and how it affects the world changes. We will try to update this blog as frequently as possible.

► What is it?

Coronaviruses are a broad range of viruses which, at one end of the spectrum cause the common cold, at the other end cause potentially fatal diseases such as MERS and SARS.

This new virus is named SARS-Cov-2, part of the coronavirus family. The disease it causes is COVID-19. DNA analysis shows it is closely related to SARS and similarly evolved from a virus affecting bats. It was identified in December 2019 when a cluster of people were diagnosed with pneumonia after visiting Huanan seafood market in Wuhan. On December 30th bronchoalveolar lavage samples from a patient with pneumonia of unknown aetiology tested positive for panBetacoronavirus at Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital. The WHO China office heard the first reports of an unknown virus causing a number of pneumonias in Wuhan by December 31st and the Chinese CDC sent a rapid response team to investigate. The first people affected were stallholders at the Huanan Seafood market in Wuhan, a market that also sells wild animals. Initially it was unclear whether there was human-human transmission as all cases were linked to the seafood market. As we all know, this then spread in Wuhan, China, and subsequently worldwide, although the speculation it was initially transmitted from zoonotic sources in a seafood market in the city has not been confirmed.

SARS-Cov-2 has been isolated in at least 166 countries and territories around the world. One can speculate that where countries have no cases this may be due to lack of testing rather than truly escaping the condition.

► How is it spread?

There remains uncertainty about the mechanism of spread. Human-to-human transmission is now undisputed although the degree of infectivity is still uncertain. Speculation is that the R0 is around 2-2.5 (i.e. for anyone diagnosed they will infect 2-2.5 people). The virus is predominantly respiratory droplet spread among close contacts (e.g. within 2m) for prolonged periods, or direct contact with infected secretions contacts (e.g. within 2m) for prolonged periods, or direct contact with infected secretions (the virus has been isolated in most bodily secretions including faeces - time to close that lid when flushing...). It can survive on surfaces outside the body, although for how long is unclear. It is assumed to behave like other coronaviruses which can last for hours to several days depending on the conditions.

This would be a good point to define what close and casual contacts actually means.

Close contact

> 15 minutes face to face contact with confirmed case in the period extending from 24 hours before the onset of symptoms.

Or

Sharing of a closed space with a confirmed case for a prolonged period (eg more than 2 hours) in the period 24 hours before the onset of symptoms.

Casual contact

Less than 15 minutes face to face contact with a symptomatic confirmed case extending from 24 hours, or sharing a closed space with a symptomatic confirmed case for less than 2 hours.

Healthcare workers in full PPE are not considered at risk.

► What is the incubation period?

The average incubation period is 5-7 days but it is very variable and some reports are that it can range from 1-14 days.

People are considered to be infectious when symptoms manifest. Currently there is no data on patients transmitting the disease without symptoms, although viral shedding has been found in the 1-2 days prior to symptoms and for up to 2 weeks in respiratory samples and 4-5 weeks in faeces. The significance of this shedding regarding infectivity is currently uncertain. Concern remains that people may be asymptomatic vectors (there are a handful of case reports showing this to be the case).

Transmission is droplet but can be airborne with aerosol-generating procedures. Contact with contaminated hands, surfaces or objects and in some cases there is faecal shedding with undetermined significance. The virus likely remains on surfaces for up to 48 hours, possibly longer on some surfaces, and requires detergent cleaning followed by disinfection.

► What are the clinical features?

The main features are fever, cough or chest tightness, and dyspnoea. However, a paper published in the BMJ shows that patients may well have none of these - fever was present in 77%, cough 81%, fatigue/myalgia 52%, headache 34%, diarrhoea in 8%. The data was collected from patients admitted to hospital so it is very possible that many in the community will have minor symptoms only and none of the above. This will make it impossible to distinguish between coronavirus and 'normal' infections.

Indeed it appears that 80% will have mild symptoms (or none), 15% will be severely unwell, 5% critically unwell.

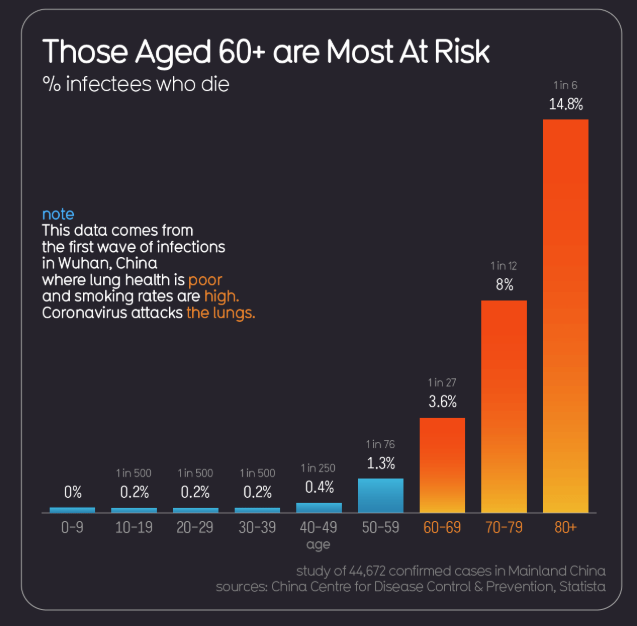

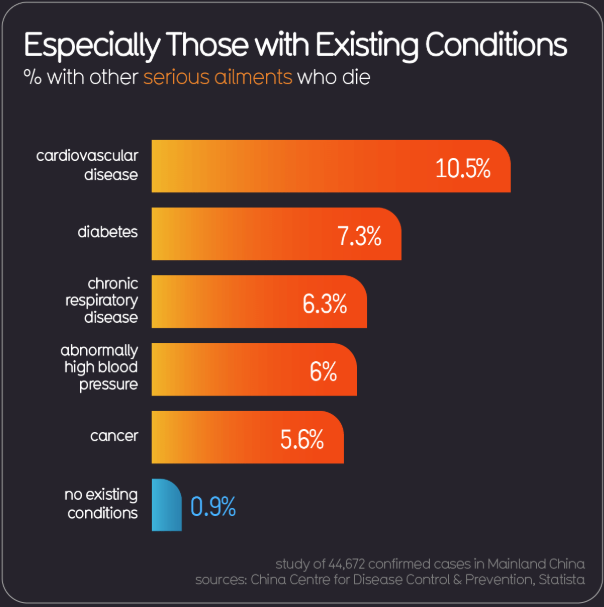

The most at risk are the elderly (particularly >80yo) and those with significant co-morbidity. Interestingly children appear to be rarely affected, although it is still possible for them to be seriously ill, and is not clear whether asymptomatic children can still be vectors for disease. Pregnant women were high risk during the swine flu outbreak but so far this hasn't appeared to be a particular issue for COVID-19.

In Chinese patients admitted to hospital sepsis was seen in 59%, respiratory failure in 54%, Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome 31%, heart failure 23%, septic shock 20%, coagulopathy 19%, acute kidney injury 15%... the list goes on. 25% had ICU admission, with an average ICU admission length of 8 days. It becomes clear how secondary care resources will be stretched, although it is worth reiterating this study was looking specifically at unwell admitted patients and is in no way representative of what we are likely to see in general practice.

One important piece of information published in The Lancet is the time from onset of symptoms to serious illness. The median time to hospital admission is 7 days, SOB 8 days, ARDS 9 days and ICU admission 10.5 days. The clear learning point here is that safety netting, warning patients to monitor for escalating symptoms, is critical - if we see an infected patient at day 3, four days later may be a very different picture.

► What is the prognosis?

Johns Hopkins CSSE is a useful website which shows active numbers on a worldwide scale.

This is the million-dollar question and very hard to answer meaningfully. Mortality is thought to be around 1-2%, some reports have suggested slightly higher but this is likely to be biased through testing of mostly high risk individuals. Given there appears widespread transmission in the community, the number of proven cases will be an underestimate of true disease (although we don't know by how much) and the real case fatality rate is presumably lower.

However, in the elderly population, the mortality rate is significant at around 20%.

► Who should be tested?

Recommendations on testing are constantly changing.

Please refer to your local state guidelines.

NSW COVID-19: Updated advice for health professionals - Diseases

Victoria Health services and general practice - coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

South Australia Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): information for health professionals

Western Australia COVID clinics

Northern Territory Coronavirus (COVID-19) updates – NT Government – SecureNT

Queensland Information for Queensland clinicians and healthcare workers—novel coronavirus (COVID-19)

Tasmania Coronavirus | Public Health

Federal Government Coronavirus (COVID-19) health alert

In summary, most States and Territories are testing those that are symptomatic only plus those with travel history or close contacts with someone diagnosed.

Anyone returning to the country is now to be in self-isolation for a period of 14 days. And anyone travelling into Tasmania must observe the same seld-isolation period.

Good Hygiene practices are paramount.

What is self isolation?

There are some good handouts for patients.

https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-isolation-guidance

Stay on your own. Have food brought to you.

Do not go outside or to public gatherings.

You do not need to wear a mask unless symptomatic.

If you do need to leave the house to get medical care then wear a mask.

You can go into your garden to get outside.

► How is testing done?

Testing is predominantly with PCR Testing and only available is specific laboratories. Nose and throat swabs, plus sputum if possible, are preferred. Turn-around time is variable depending on where you live. We have no definitive data on sensitivity and specificity but it would appear that the test is very specific but not sensitive.

What seems unclear is at what point a test becomes positive. At the point of symptoms there will be plenty of viral shedding and the test should be accurate, but a negative test cannot be relied upon if a high risk patient is asymptomatic but still in the incubation period. This leads us on to the next question...

► What should we do with high risk patients who test negative? (the test is specific but lacks sensitivity, which is the point you make if the story is good but test negative then this could be the sample was taken badly or the test failed to pick it up)

- Patients with travel need to isolate for 14 days

- For contacts of a proven case they need to continue to isolate until 14 days after the contact

- If any of these groups develop new symptoms in the meantime they should contact 1800 020 080

► Are there treatments?

Whilst a range of treatments such as anti-retrovirals for HIV and Ebola, oseltamivir, monoclonal antibodies (using AI to quickly identify possible effective ones based on viral protein profiles) and more complex ICU-based interventions are being tested, at this point nothing has been clearly beneficial and supportive therapy remains key.

Vaccines have already been produced, which is absolutely remarkable, but require human testing, ideally RCTs, and are unlikely to be widely available (assuming they work and don't have nasty side effects) until 2021.

► What should practices do?

Again there are a variety of responses and different General Practices instituted their own practices.

The telehealth codes have the potential to reduce the need for face-to-face contact and also protecting ourselves and our staff.

https://www.avant.org.au/news/new-coronavirus-medicare-telehealth-item-numbers/

There are several elements that we can consider to protect our patients, staff and ourselves:

- Consider triage of all patients in general practice using telephone or internet. This will call for pragmatic medicine, something GPs excel at. Clearly some patients will continue to require face-to-face appointments. Our core work will still continue. Practices and localities will need to decide how to manage potential COVID-19 cases that do require assessment.

- If patients with possible COVID-19 present at the practice, and are well, they should be directed home to self-isolate. If unwell some options are

- Telephone consultation

- Practices should consider identifying a dedicated room for isolation, declutter it to facilitate cleaning, and have easy access to PPE (which can be challenging at this time).

- Or send patients directly to the COVID/Temp Clinics at your local hospital if available.

- Encourage good hand hygiene in patients and staff attending the practice to reduce the risk of cross- contamination.

- Have clear information at access points to the surgery with the latest guidance on what to do (i.e. don't just turn up, call and we'll contact you).

- Consider a screen when booking appointments

Social distancing is advised and now gatherings of more than 100 have been banned. Care homes are also on lockdown which seems sensible given these are the most vulnerable and, at the height of the pandemic, the least likely to have intensive treatment.

Many companies have instituted ‘working from home’ regimes.

► Do face masks help?!?

Complicated and hampered by confusing data involving a plethora of different types of face masks. The European Centre of Disease Prevention and Control recommends for suspected or proven cases the ideal face mask is an FFP3 (or an FFP2 if the former is not available). These are fitted face masks which usually have a valve to enable prolonged use.

In primary care we have been given simple surgical masks. Interestingly a JAMA editorial highlights research showing if clinician and patient wear these masks the protection is as good as an FFP3 mask when having prolonged exposure to infected patients.

In the general population it is felt that such masks are unlikely to reduce transmission.

It is probably reasonable to put a mask on a high risk patient rather than all wearing masks and leaving them to cough.

► Do we know how the disease will progress?

Time to get out your crystal balls. Experts have used modelling data and the situations in Wuhan and northern Italy to try and build a picture of how the infection will spread but nothing is certain. The main points:

It is likely to spread with escalating numbers of cases. The number of cases is likely to increase rapidly over the next few weeks. The duration of the outbreak is unclear but we will probably see high numbers of cases for several months. Slowing the rate of increase is helpful to ease winter pressures on health services, to allow time to build resources such as testing kits, protective equipment, etc., and to spread cases over a longer period.

Lessons can be taken from the Chinese governments' management of the situation with a large scale, very restrictive lock-down. Whilst extreme, cases in the country are now falling and wide-spread transmission throughout China appears to have been prevented. Italy appears to have gone in the same direction.

This may be difficult to implement in other Western societies, plus would have significant implications on economies, which in the end could also cause loss of life. These will be discussions for our politicians guided by the experts.

There is even doubt that these methods will have a lasting benefit and when the restrictions are lifted a further rise in cases is likely. Only time will tell but it will build on our knowledge for the next pandemic.

This is a graph mathematically formulated from one of our colleagues Dr Michael Tam who has given permission for all to share. It is based on worldwide data and shows what we may be facing over then next few months.

**Information correct as of Wednesday 18th March 2020** www.nbmedical.com - Content localised by Dr Jo Bruce.

The Medcast medical education team is a group of highly experienced, practicing GPs, health professionals and medical writers.

Become a member and get unlimited access to 100s of hours of premium education.

Learn moreAnthony is a retired engineer, who is compliant with his COPD and diabetes management but has been struggling with frequent exacerbations of his COPD.

Whilst no longer considered a public health emergency, the significant, long-term impacts of Covid-19 continue to be felt with children’s mental health arguably one of the great impacts of the pandemic.

Your next patient is Frankie, a 5 year old girl, who is brought in by her mother Nora. Frankie has been unwell for the past 48 hours with fever, sore throat and headache. The previous day Nora noticed a rash over Frankie’s neck and chest which has since spread over the rest of her body.