Wearables and AF: how smart are smartwatches?

Wearables, such as smartwatches and fitness trackers, are everywhere - and now they’re tapping into more than step counts or exercise minutes. Many of your patients may already be using these devices to estimate their VO2 max and detect irregular heart rates and rhythms, including atrial fibrillation (AF). As GPs, it’s worth considering: are these devices a useful early detection tool in primary care, or just more noise?

How wearable tech detects atrial fibrillation

Most wearables take non-invasive measurements using either photoplethysmography (PPG) or a single-lead ECG.

PPG is a well-established technology that uses reflected light to detect pulsatile changes in blood volume. Software algorithms are then used to extrapolate heart rate and other physiological parameters.

Newer generation ECG-capable devices use sensors, typically on the underside of the device and around the frame. When these sensors are both in contact with the patient and the ECG app is opened, they record a 30-second trace (Figure 1). This generates an ECG similar to a single-lead (or Lead I) ECG. As other waveforms cannot be visualised on a single-lead ECG, ischaemic changes and other cardiac conditions cannot be assessed with wearable technology.

Figure 1. How to take an ECG reading on an Apple SmartWatch

(image credit: https://support.apple.com/en-au/120278)

Both approaches rely on algorithms to interpret results. PPG and ECG technology can be influenced by the limited capacity of the algorithm, heart rates that are too high or too low, and other underlying anomalies such as motion, environmental interference (e.g. electrical signals from nearby devices), poor skin contact and skin-related factors such as sweating and tattoos.1,2

According to Australian guidelines, the gold standard for AF diagnosis remains a 12-lead ECG showing irregular RR intervals and absent P waves, sustained for at least 30 seconds.3

How accurate are they at detecting AF?

While PPG wearables are a useful screening tool, they’re not yet a substitute for clinical confirmation by 12-lead ECG.4 Devices detecting AF using a single-lead ECG can be diagnostic after interpretation by a clinician.4

This may seem surprising, given that systematic reviews and meta-analyses of commonly used wearables have reported high sensitivity (up to 96%) and specificity (about 94%), and described them as non-inferior in the detection of AF, compared to medical-grade monitors.5–7

Yet, these same studies also acknowledge that a significant limitation of consumer wearable devices for AF screening remains the relatively high rate of inconclusive readings (up to 30% reported in some studies), even among populations where positive predictive values for AF are higher, such as patients who are older or who have risk factors for AF.5,8–10 Inconclusive results produced from a wearable device can ‘hide’ false negative and false positive readings.5,11,12

What about devices available in Australia?

Since 2021, the TGA has approved several software applications for use with consumer-wearable devices to support the detection of irregular heart rhythms through PPG, or by recording cardiac signals using a single-lead ECG.13–21 However, due to variability in device performance and the significant rate of inconclusive results, it's crucial to corroborate wearable device findings with standard diagnostic methods, such as a 12-lead ECG.

Healthcare professionals need to guide patients on the appropriate use of these devices and interpret the data within the broader context of each patient's clinical needs.

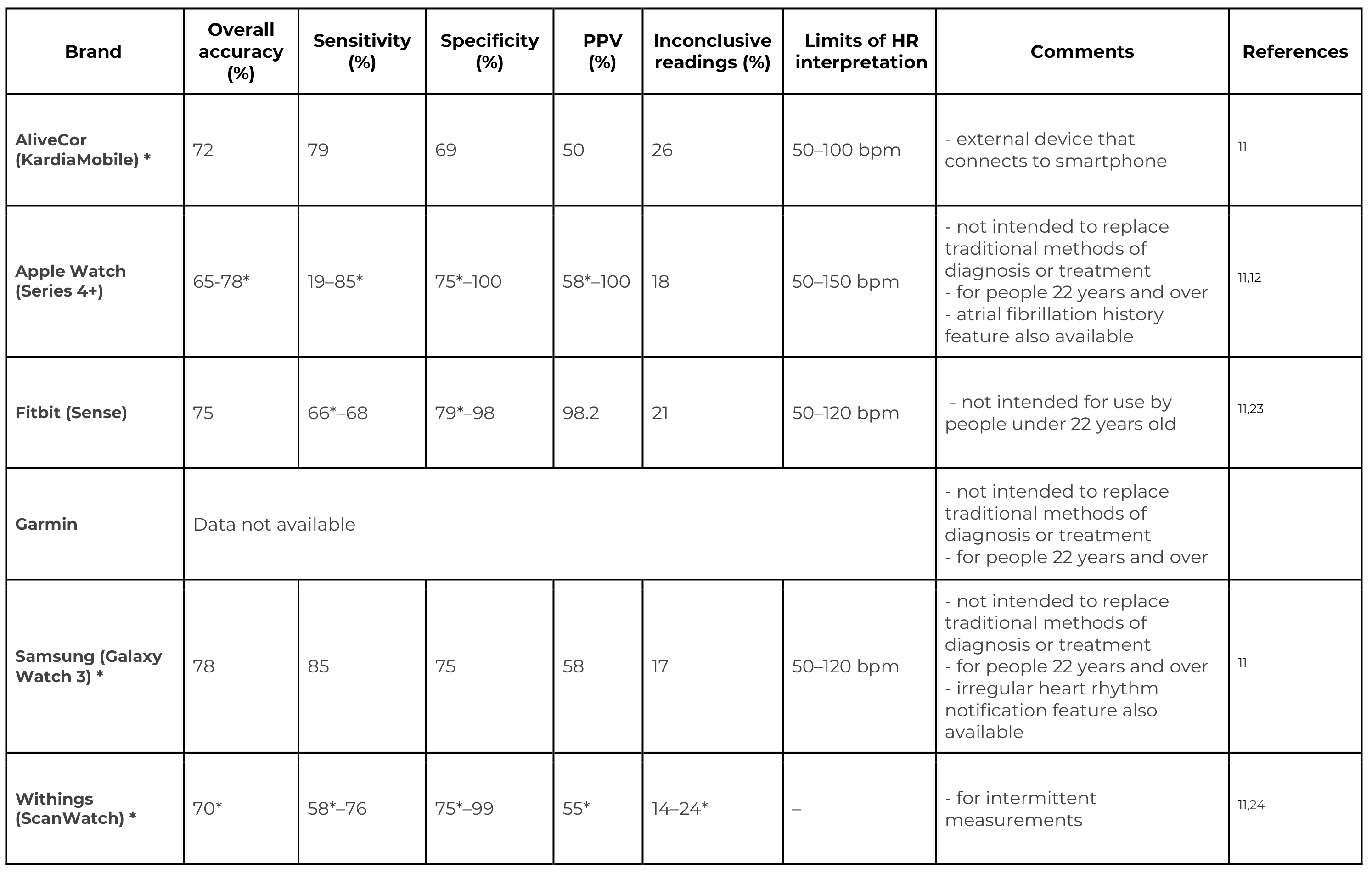

Table 1 summarises the key findings from recent prospective, comparative trials of single-lead ECG consumer wearables that are also TGA-approved. Given the pace of technical change, software updates may mean that the data has already been superseded.

Note: The tabulated information comes from multiple trials and should not be used to directly compare products.

Table 1: Summary of wearable device technology using single-lead ECG for AF detection (TGA approved)

*Intention to diagnose/screen measures; inconclusive results included; bpm = beats per minute; PPV = positive predictive value

Are your patients smartwatch-ready?

For some people, the constant flow of digital health information can be a source of encouragement to engage with and maintain healthy behaviours. And for those patients with intermittent symptoms, the ability to continuously monitor has the potential to provide clinically actionable data. The downside to this is technologies that heighten awareness and attention to fluctuations in heart rate and rhythm may increase anxiety in susceptible individuals and prompt unnecessary medical care.25

Patients need to be educated on the abilities and limitations of these devices, so they understand they are not a gold standard diagnostic tool and are most helpful when used under professional supervision and after thorough instruction.

When talking to patients about wearable devices for AF detection:

-

educate on the role of information and how and when to record an accurate trace

-

guide them on how to export and share recordings as needed

-

encourage communication so they are empowered to seek clinical advice if their device flags an irregular rhythm

You can learn more about stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation through our recently launched national education program here.

References

1. Scardulla F, et al. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2023.113150

2. Apple Support. Accessed 22 May 2025. https://support.apple.com/en-au/120278

3. Brieger D, et al. (2018). https://doi.org/10.5694/mja18.00646

4. Van Gelder IC, et al. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehae176

5. Zarak M S, et al. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42444-024-00118-5

6. Elbey MA, et al. (2021). https://doi.org/10.4022/jafib.20200446

7. Prasitlumkum N, et al. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acvd.2020.05.015

8. Perez, MV. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacep.2022.03.018

9. Teh AW, et al. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacep.2022.10.036

10. Scholten J, et al. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjdh/ztab104.3047

11. Mannhart D, et al. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacep.2022.09.011

12. Ford C, et al. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacep.2022.02.013

22. Chang PC, et al. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2022.02.002

23. Lubitz SA, et al. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.060291

24. Badertscher P, et al. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hroo.2022.02.004

25. Rosman L, et al. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.123.033750

The Quality Use of Medicines Alliance is a unique consortium of health sector organisations representing quality use of medicines expertise, education providers, researchers, colleges, peak bodies, member-based organisations, and consumer groups. Funded by the Australian Government under the Quality Use of Diagnostics, Therapeutics and Pathology (QUDTP) Program.

GP Dr Kate Annear and Clinical Psychologist A/Prof Aliza Werner-Seidler discuss practical strategies for engaging young people, conducting psychosocial assessments, and using lifestyle, social, psychological and digital interventions to support mild to moderate depression and anxiety in young people.

With one in three young Australians experiencing a mental health condition each year, and suicide remaining the leading cause of death for 16 to 24-year-olds, the way clinicians approach antidepressant use in teens and young adults has never been more important.

Discover practical strategies for GPs to identify and manage anxiety and depression in adolescents, balancing non-pharmacological care with thoughtful, evidence-based prescribing when needed. Find out how the Quality Use of Medicines Alliance is helping health professionals navigate this complex area with new clinical tools, national education programs and expert-led insights.